I was always charmed by the idea and the practice of algorithm-heavy programming. The heavy lifting, making seemingly complex and daunting tasks run like

That’s what got me into programming 20 years ago, as I started ploughing my way through lines of TurboPascal code, and it’s what keeps me loving programming nowadays as well. Since that time, I underwent VB 6.0, learned a bit of Java, some VB.NET, dabbled in VBA, fell in love with C#, learned to hate JavaScript, played with meta-programming (Rascal) and functional programming (Haskell) in university, and because of my study endeavours in the field of data science and AI, am experiencing a fair bit of Python and R as well.

Now, because all of this, I do spend a fair amount of time wandering through sites like TopCoder, HackerRank, CodeFights. You know, all those nerdy coding websites for developers that don’t particularly enjoy learning all the ways to create flashy front-end webdesigns. The type of programmer who believes that high quality code, efficiency and performance do actually matter, and is convinced that mastering those skills will set you up for a rewarding career in the long haul (how naive we are, we’d better stick with current trends and learn Angular2 right? NO!! Although that’s a topic for another post). I do not proclaim to be great at all this stuff, but I like a challenge from time to time. I came about such a challenge very recently, and after being presented with the possible solution, I got that typical thought I get sometimes. It goes something like this:

“Yeah, you can do it like that, but surely there’s a better way, I just don’t remember it right now, but let me dig into it for a minute and I’ll get right back to you.”

We all have those moments. Now let’s face it, unless you work at Google, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon or some other company where you work through problems with complexity similar to theirs, you simply will not get confronted with algorithm-heavy programming. That’s a reality. Now for most people, that’s no problem at all. Most people don’t have the ambition to do so, and will spend their careers not once having to solve such a problem. But let’s ignore those people for now (sorry guys ;-) ) and start from the philosophy that, although you may not need to know all sorting/searching/pathfinding algorithms for your day-to-day work or side-projects, you can be damn sure that knowing them will make you a much better programmer. Additionally, depending on your goals and ambitions, it does increase your chances of getting involved in more complex areas of development, with higher impact, and brings you in contact with smart and highly skilled people.

Obviously, you forget a lot of the details of that stuff if you don’t work through it frequently enough. So, from time to time, you owe it to yourself to pick up a book or online course and brush off those skills. It sure beats sitting in your couch and watching tv. The question is: where to start? You can’t jump in the overly complex stuff rightaway. Although sorting and searching algorithms are a good start, my recent experience is a possibility to leave the beaten path a bit, and introduce an alternative starting point for getting into algorithms.

The challenge

So, what’s the deal? Well, the deal/assignment/challenge was as follows:

“Get me all the prime numbers below 100!”

Now, after reading that sentence, 95% of you will ignore the rest of this post and will be on their merry way. 4.9% will think

“Allright, that’s nice and all, but that’s a beginner problem…”

and move on to more interesting areas of the internet. Can’t blame them, since in terms of algorithms, this is indeed a beginner problem. The goal, however, is to shed some light on the way to go about thinking about any algorithmic problem, instead of just giving you the solution to it and pack up. No matter how complex the problem is, the way to approach it is often very similar. So, for the 3 programmers that are ticked off, and the 2 recruiters that spend their days browsing the profiles of all developers, hoping to snatch them away (you know who you are), and that are interested in someones thought process, here goes…

The problem area

First off, we might want to reiterate what the hell a prime number is. Most of us will obviously know, but to really make sure we understand completely and don’t forget about edge cases, let’s just define the problem area here.

A prime number is a natural number greater than 1 that has no positive divisors other than 1 and itself.

So, that’s pretty clear.

- Natural number.

- Greater than one.

- No positive divisors besides itself and 1.

Ok, now that’s obvious, let’s just have a first go at this…

A naive solution

No, that’s not an insult to the people that will come up with the solution I’ll explain below. A naive solution to a problem is basically the algorithm that solves the problem with no particular aim towards optimization. It’ll get the job done, but that’s it most of the time.

So one possible naive solution is the one below. By the way, I’m writing this in C#, Java or C++ programmers out there will have similar constructs for the collections I use. In general, any C-type language connoisseur (see how I used a relatively rare word there?) will have no problems understanding at least the syntax of my coding gibberish. Also, note that I’m using the pinnacle of front-end splendor (a console application), so that’s why my functions are static. If you don’t like that, go back and read the intro again, you’ll realize you should have known.

public static long[] SimplePrimes(long n)

{

if (n < 2) { return new long[] { }; }

var primes = new List<long>();

for (var i = 2; i <= n; i++)

{

var isPrime = true;

for (var j = 2; j < i; j++)

{

if (i % j == 0)

{

isPrime = false;

break;

}

}

if (isPrime) { primes.Add(i); }

}

return primes.ToArray();

}

That’s a pretty raw version, and as far as I can see it’s pretty much the most horrible solution that still gets the job done. Of course, this should immediately trigger the

“That can’t be ideal…”

itch that you just have to scratch, but it’s a place to start from. So, in short: what happens here?

- Right off the bat, I’m returning an empty array in the case that n is smaller than 2. Primes are greater than 1, remember?

- Then we start looping i from 2 to n, which is our upper limit. Those are basically the numbers we have to test for being prime.

- In our loop, we set isPrime to true, to assume i is a prime.

- In an inner loop (red alert) we loop from 2 to i (well, i-1 really) and we check if i mod j equals 0. If that’s the case, guess what, i is not prime, we set isPrime to false, and we can break out of the loop. In the case of i being 2, the inner loop doesn’t even run once, so 2 gets added, we’re safe there.

- If our flag survived the inner loop, i is prime, so we add it to the list.

Some issues

Now, obviously this is not a particularly smart way to go about things. Whenever you start doing inner loops, things potentially get dangerous. So we have something to inspect: what really happens in the inner loop? First of all, it’s not really O(n²). The inner loop does not loop all the way to n (in fact, that wouldn’t even work), so that is at least something. Some immediate observations though:

- The outer loop runs from 2 to n. I don’t like that. Any n lower than 2 made us jump out of the function already. So we know n is at least 2 by the time we get to the loop (if we ever get there). So why not already add 2 to the list of primes, and start looping from 3? It’s a detail, but it counts.

- Building on that, we know that even numbers higher than 2 can not be prime. So instead of testing each even number, why not increase i with 2 every time, so i will be 3, 5, 7, 9, …? That already saves us half the trouble. I like that.

- Now for the optimization that was in the solution that I got presented, and that actually sparked my desire to write this blog. Concerning the inner loop: we don’t really need to loop all the way to i. Let’s say i equals 17, so we’re testing 17 for being prime. We don’t have to test 17 % 2, 17 % 3, 17 % 4 all the way to 17 % 16. It’s enough to let the inner loop go to the square root of i. If we test all numbers until there, we know we tested all factors. In itself a pretty strong optimization, since it makes sure we don’t have O(n²), but basically O(n* sqrt(n)). The outer loop runs n times, the inner one max sqrt(n) times.

- Just a thought: when i is a prime, you’d have to perform the inner loop all the way from 2 to i. If i is not prime, you break out of the loop much sooner. So it’s funny that a succesful find is much more expensive. Just a thought on the side.

- Although the inner loop does not go all the way to n, it does get progressively worse the higher i gets. Sure, we avoid true quadratic complexity, but it just doesn’t feel right to me. Now, we are only running to 100, so we’re not going to prove much. In short, I’m thinking

“Who cares about all primes below 100? I’d have to write a pretty horrific piece of code for that to run slow… No, I’ll focus on primes below 1.000.000 (for starters). That’ll give me a better indication about how efficient the code runs.”

In case you wonder how this actually performs, bear with me, the results are shown at the bottom of this post, together with the results of the optimizations that I did. But first, let’s take the remarks into account and refactor this into something that is likely to do a much better job.

Take 2

If we implement optimizations for remarks 1 to 3 (and some extra stuff) from the list above, we achieve the following code:

public static long[] OptimusPrime(long n)

{

if (n < 2) { return new long[] { }; }

if (n == 2) { return new long[] { 2 }; }

if (n == 3) { return new long[] { 2, 3 }; }

var primes = new List<long>() { 2, 3 };

for (var i = 5; i <= n; i += 2)

{

var isPrime = true;

for (var j = 2; j <= Math.Sqrt(i); j++)

{

if (i % j == 0)

{

isPrime = false;

break;

}

}

if (isPrime) { primes.Add(i); }

}

return primes.ToArray();

}

The check for n being smaller than 2 has stayed the same. For giggles, I added 2 silly little micro-optimizations in the case of n being 2 or 3. In those cases, we already return with finished arrays.

Only if n is 5 or higher, does the actual algorithm take place. We already add 2 and 3 to the list, since those are obviously prime and always in the list if we made it so far. Then we start looping from 5, and add 2 for every iteration, ensuring we stick to testing odd numbers.

Concerning the inner loop, we only run to the square root of i, cutting the number of iterations of that loop way down.

Without even presenting you with test results right now, you can already tell that this implementation will be way more efficient. However, that’s not what I was thinking when faced with this solution (although the original one was slightly less optimized than this), since in the back of my mind, I remembered parts of a much better solution, with much higher efficiency.

So let’s try that again

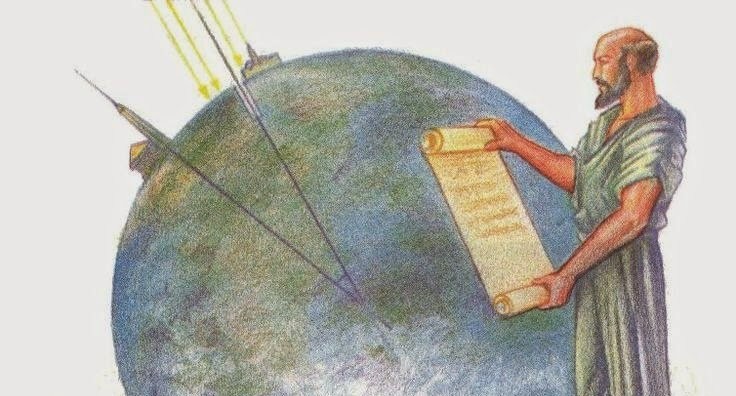

I did remember a much better solution that I learned once, but kind of forgot. Weird as this may sound, I’m not calculating prime numbers in my spare time (except for this one time I guess), so this one was pretty rusty. After checking online and brushing off some stuff, I remembered the Sieve of Eratosthenes algorithm, which is a pretty old but simple algorithm to calculate primes in a very efficient way. Of course, you can just copy an implementation from a website and go with that, but I would strongly advise you to

NOT EVER DO THAT

It may be (partly) wrong and you won’t learn a thing. And frankly: if you think spending your free time checking out algorithms on prime numbers and writing a blog post about it is a bit weird, how does copying one from the internet make you feel? That’s just sad.

The way the algorithm works is pretty simple actually. You create a list of candidate numbers, from 2 all the way to your upper limit. Then you start with 2. You mark it as prime, and then mark all its multiples as non-prime (since they are composite numbers after all). You then search the first non-marked number in the list. That will be a prime, and you then mark all its multiples as non-prime. You repeat this until you can’t find any unmarked numbers in the list. All remaining unmarked numbers are the primes.

The algorithm as I interpreted it:

public static long[] SieveOfEratosthenes(long n)

{

if (n < 2) { return new long[] { }; }

if (n == 2) { return new long[] { 2 }; }

if (n == 3) { return new long[] { 2, 3 }; }

// Fill array

var numbers = new long[n];

for (var i = 1; i < n; i++)

{

numbers[i] = i + 1;

}

for (var i = 1; i <= Math.Sqrt(n);)

{

// Calculate the current number

var curNr = i + 1;

// Set all multiples of curNr to 0 (they are not prime)

for (var j = (long)Math.Pow(curNr, 2) - 1; j < n; j += curNr)

{

numbers[j] = 0;

}

// Find the next unmarked (!= 0) entry in the array

i++;

for (var j = i; j < n; j++)

{

if (numbers[j] != 0)

{

i = j;

break;

}

}

}

return numbers.Where(e => e != 0).ToArray();

}

What in the hell happens here? Well, let’s go through it step by step:

- First, we go through the special cases where n is lower than 2, or equals 2 or 3.

- Then we fill a numbers array from one to n.

- Then we start looping until we reach the square root of n, basically for the same reason as we did when optimizing the simple algorithm.

- Now, again we do an inner loop, which would be reason to get worried. The thing is though, we only start from the exponent of the current number. The reason for this lies in the fact that all numbers below that would already have been marked as 0 by the inner loops for lower numbers. This combination of a limited outer loop and a limited inner loop makes for a very (guess what) limited number of operations that get executed, which in turn catapults the efficiency way up.

- After setting all multiples of the current number to 0, we go and look for the next number in the list that is not marked as 0.

You will see (very shortly) from the results that you get real big gains in execution time with this algorithm. Although it is definitely not the fastest algorithm possible, it is a really simple way to tackle the problem, with pretty good results.

Now, I wouldn’t be the idealist I am if I didn’t want to optimize this even further. Remember when I optimized the simple algorithm to make sure it only considered odd numbers (besides 2)? Well, we could do that here as well! And we should! Now, just for fun, I’m not even going to explain this one. I’ll leave it up to you to figure this one out. The obvious issue is that you will need to do some calculations to determine the right positions. If you visualize your array though, you’ll get it pretty quickly. The code looks as follows:

public static long[] OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes(long n)

{

if (n < 2) { return new long[] { }; }

if (n == 2) { return new long[] { 2 }; }

if (n == 3) { return new long[] { 2, 3 }; }

// Calculate the number of elements in the array

var elements = n % 2 == 0 ? (n - 1) / 2 : n / 2;

var numbers = new long[elements + 1];

// Already put 2 in the array, followed by all odd numbers // starting from 3

numbers[0] = 2;

for (var i = 0; i < elements; i++)

{

numbers[i + 1] = 3 + (i * 2);

}

var max = (long)Math.Sqrt(numbers.Last()) / 2;

for (var i = 1; i <= max;)

{

// Calculate the current number

var curNr = i * 2 + 1;

// Set all multiples of curNr to 0 (they are not prime)

for (var j = i * curNr + i; j <= elements; j += curNr)

{

numbers[j] = 0;

}

// Find the next unmarked (!= 0) entry in the array

i++;

for (var j = i; j < elements; j++)

{

if (numbers[j] != 0)

{

i = j;

break;

}

}

}

return numbers.Where(e => e != 0).ToArray();

}

Results

So, after all that, how do those 4 algorithms actually stack up? Well, I decided to run them together. Let’s look at how they perform when setting the n-variable to 10 and keep on going to a higher order of magnitude, until n equals 1.000.000. The results quickly reveal the immense differences in speed (first measure is milliseconds, second one is ticks):

4 primes <= 10 in 0ms, 787ts (SimplePrime)

4 primes <= 10 in 0ms, 889ts (OptimusPrime)

4 primes <= 10 in 3ms, 9,427ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

4 primes <= 10 in 1ms, 3,171ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

25 primes <= 100 in 0ms, 49ts (SimplePrime)

25 primes <= 100 in 0ms, 18ts (OptimusPrime)

25 primes <= 100 in 0ms, 46ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

25 primes <= 100 in 0ms, 10ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

168 primes <= 1,000 in 0ms, 2,342ts (SimplePrime)

168 primes <= 1,000 in 0ms, 268ts (OptimusPrime)

168 primes <= 1,000 in 0ms, 71ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

168 primes <= 1,000 in 0ms, 51ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

1,229 primes <= 10,000 in 51ms, 129,781ts (SimplePrime)

1,229 primes <= 10,000 in 2ms, 5,501ts (OptimusPrime)

1,229 primes <= 10,000 in 0ms, 503ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

1,229 primes <= 10,000 in 0ms, 299ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

9,592 primes <= 100,000 in 3,848ms, 9,742,503ts (SimplePrime)

9,592 primes <= 100,000 in 57ms, 145,474ts (OptimusPrime)

9,592 primes <= 100,000 in 1ms, 4,705ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

9,592 primes <= 100,000 in 1ms, 2,866ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

78,498 primes <= 1,000,000 in 337,699ms, 854,801,981ts (SimplePrime)

78,498 primes <= 1,000,000 in 1,467ms, 3,715,209ts (OptimusPrime)

78,498 primes <= 1,000,000 in 24ms, 63,136ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

78,498 primes <= 1,000,000 in 13ms, 33,610ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

You can see that the Eratosthenes-algorithm totally slays the simple algorithm from the moment n equals or is higher than 100, and it gets progressively worse for the simple algorithm from there.

Now for the big point I was trying to make all along: sure there is a big difference between the naive prime algorithm (SimplePrime) and the optimization (OptimusPrime, which was even more optimized than the suggestion I got). The difference is immense. However, from the moment n is 1000 or more, that so-called optimization becomes pretty damn slow itself! Compare the optimized basic algorithm with the basic sieve algorithm and notice the incredible difference in speed. Now that is what I call a fast algorithm! Forget about calculating a 100 primes. How about +75.000 primes in 24ms compared to 1.4 seconds…?

Additionally, to really hammer the point home, take a look at the gains that I got from optimizing the sieve algorithm even further! You really have to look at them side by side, and make n even bigger to really appreciate what you can get there:

1,229 primes <= 10,000 in 4ms, 10,505ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

1,229 primes <= 10,000 in 1ms, 3,614ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

9,592 primes <= 100,000 in 3ms, 8,469ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

9,592 primes <= 100,000 in 1ms, 4,418ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

78,498 primes <= 1,000,000 in 34ms, 86,399ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

78,498 primes <= 1,000,000 in 17ms, 45,368ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

664,579 primes <= 10,000,000 in 353ms, 894,920ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

664,579 primes <= 10,000,000 in 185ms, 469,128ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

5,761,455 primes <= 100,000,000 in 3,406ms, 8,622,256ts (SieveOfEratosthenes)

5,761,455 primes <= 100,000,000 in 1,860ms, 4,708,271ts (OptimusSieveOfEratosthenes)

That’s 5.761.455 prime numbers, calculated in almost the same time as the optimized basic algorithm took to calculate 78.498. That’s almost 2 orders of magnitude right there. Case closed.

O

The reason for all of this is obvious. The simple algorithm has close to quadratic complexity. Now, granted, for getting primes under 100 or even 1000 or 10.000, you won’t notice that. You could defend that. But the point of an algorithmic challenge like this is being able to find a solution that may not be perfect, or the best solution (the best solutions as far as I’m aware of are optimized AKS-algorithms, for which the original authors received a Gödel prize in 2006, we’re not quite aiming for that), but we should always aim for a solution that keeps standing when numbers get fairly high. A quadratic solution is not that. In fact, that’s pretty aweful.

The optimized basic algorithm still has O(n* sqrt(n)) complexity. The Sieve of Eratosthenes has O(n (log n) (log log n)) complexity. Although it’s not extremely difficult to analyze what’s happening here and go over how many iterations the inner loop does per outer loop, I’d suggest you read up on it here.

As I said, this algorithm is definitely not the fastest. It can be optimized much further than I did (although that would raise the complexity quite a bit), and even then other sieves can outperform it. I do feel though, that this is a great first algorithm to learn besides the obvious search and sort algorithm every courses starts beating you over the head with. Although they are important, this is a nice alternative. Just remember: although it’s very tempting to give up after a first attempt, don’t! Stick at it, take a step back and think about the problem before coding it out. You’ll learn the most, and a bit of headache never killed anyone ;-)

If you notice anything silly or sloppy in this explanation, or have remarks or questions, do let me know! I’d love to hear your thoughts on this!