The end-of-year holiday season is always the time where Advent of Code comes out. It’s an annual event in December that provides a series of daily programming puzzles, designed to challenge and entertain programmers of all skill levels. It runs from December 1st to December 25th, with a new puzzle released each day. Solving the first part unlocks the second, which is often a twist or an extension of the first part. The puzzles typically start easier in the early days and become progressively more challenging as the event progresses.

Solutions are time-sensitive, and participants can compete on a global leaderboard for the fastest solutions. The puzzles are designed to be fun, often involving creative themes or storylines. They encourage problem-solving, algorithm design, and optimisation skills. In short: a must for everybody that looks for an out during those boring days off. Many people use it to brush up on their skills, learn a new language, or just for the sake of the challenge.

Since the language of choice is free, and people will be comparing their implementations, you know the inevitable happens: a lot of back-and-forth regarding what language is the best/most efficient/easy to write. Since my language of choice is Rust, I was interested in trying to compare an implementation in Rust to one in Python, and see how far I could take it. As a teaser: in the end, we’ll be processing 100 million lines of data, about 1.3GB, in less than a second.

The assignment

I got late to the party this year since I was learning some other stuff, but I saw a post from Antoine Van Malleghem (check out his work if you like robotics and golf), using the challenges of this year to learn Rust, and also comparing it with Python which is the language he already knows. I saw a lot of arguments about the fact that Rust would be faster, but Python would be easier. The usual language wars, as I said 😉. Now, this is not quite an honest comparison. We are comparing a system level compiled language, that has performance on par with C/C++, to an interpreted language where a for-loop can bring your system down. However, if you know what you are doing, you can still leverage the fact that Python is a fine glue language, to achieve more than decent speeds for some use-cases. You know where this is going.

The specific assignment was the first part of day 1 of Advent of Code, so quite a small little assignment. You can read the full problem statement, but the gist of it was quite basic. Process a text file with 1000 entries like the following:

61087 87490

31697 16584

57649 82503

75864 27659

27509 96436

sort each side, and calculate the difference between the smallest entries on each side, then the second smallest entries on each side, and so forth. Then add up all those differences to obtain the final solution for the assignment. To illustrate, if the list of entries would look like this:

3 4

4 3

2 5

1 3

3 9

3 3

the pairs and distances would be as follows:

- the smallest number in the left list is 1, and the smallest number in the right list is 3. The distance between them is 2.

- the second-smallest number in the left list is 2, and the second-smallest number in the right list is another 3. The distance between them is 1.

- the third-smallest number in both lists is 3, so the distance between them is 0.

- the next numbers to pair up are 3 and 4, a distance of 1.

- the fifth-smallest numbers in each list are 3 and 5, a distance of 2.

- finally, the largest number in the left list is 4, while the largest number in the right list is 9; these are a distance 5 apart.

To find the total distance between the left list and the right list, add up the distances between all of the pairs you found. In the example above, this is 2 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 2 + 5, a total distance of 11. Quite simple.

A matter of scale

Obviously, the basic implementation in whichever language would always be “fast enough” (whatever that means), unless you do something really inefficient. After all, we’re handling a small list of 1000 entries. The real judge of quality is how well an implementation scales. Also, quite a few people gave the comment that offloading much of the work to libraries like Pandas and Numpy, would be super fast. After all, Pandas and Numpy are implemented in C, and Python would just play its part as a “glue language”. Since I’ve got a strong positive prejudice/obsession towards Rust, I thought I would check if I could somehow improve on the results of this “glueing together of popular Python frameworks” by implementing as much as possible in Rust. A true “rewrite in Rust” exercise, so to speak.

Instead of sticking to 1000 entries, I created lists of 1k, 10k, 100k, 1M, 10M, 50M and 100M entries. I compared very basic implementations in both languages, iterated a lot and tried several things to get some decent speed out of both implementations. The chapters below will give you a rundown of all the steps I took to get the most speed out of both languages. For Rust, I leaned more towards implementing as much as possible myself (because, of course I did). On the Python side of things, I mostly used familiar frameworks like Pandas/Polars and Numpy.

In the end, though, one fundamental change yielded a 40-50% speedup in both language implementations, without depending on external frameworks. I have no doubt that the Rust/Python wizards out there can get even more performance out of this, and if you do, please let me know!

A basic implementation

Initially, I wrote and compared basic implementations in Rust and Python. The main use of this is to get a very simple implementation on both sides that we can use as a baseline and to verify the correctness of what we implemented. I started out with using nothing but the standard library in both the Rust (ok ok, I’m using anyhow, but this has no bearing on the outcome) and Python implementations.

I kept the larger input files for later optimisations, and decided to stick to a maximum of a million entries for this basic implementation. The main steps of the solution are simple:

- read the data files line by line

- parse each line by extracting both numbers and placing them in their own lists

- sort each list

- loop through both lists and calculate the distance for each entry at the same index in each list

- sum these distances

Both the Rust and Python versions will not differ substantially at all, which makes sense. Nonetheless, I will go over each implementation quickly, to make sure we’re all on the same page regarding the starting situation. All code in this section can be found in the various commits on the master branch of the repository.

The Rust code

The main code of the Rust version simply loops over all files. Per file, we build 2 lists of sorted numbers for the first and second columns of the file, respectively. We’ll then compute the sum of all distances between the entries of each list and print out the answer.

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let files = [

"./data/input_1k.txt",

"./data/input_10k.txt",

"./data/input_100k.txt",

"./data/input_1m.txt",

];

for file in files.iter() {

println!("Processing {}...", file);

let now = Instant::now();

match get_sorted_vectors(file) {

Ok((v1, v2)) => {

let distance = compute_distance(&v1, &v2);

println!(

"The answer is: {}, completed in {}ms\n",

distance,

now.elapsed().as_millis()

);

}

Err(e) => {

eprintln!("Error processing file '{}': {:?}\n", file, e);

}

}

}

Ok(())

}

The get_sorted_vectors function reads all lines in the file, and we’ll use the combination of filter_map and fold functions to split each line and parse the entries, as well as pushing all numbers in their respective vectors. Before returning the list, we sort each vector.

fn get_sorted_vectors(file_path: &str) -> Result<(Vec<i32>, Vec<i32>)> {

let lines = read_lines(file_path)

.with_context(|| format!("Failed to read lines from file: {}", file_path))?;

let (mut col1, mut col2): (Vec<i32>, Vec<i32>) = lines

.map_while(Result::ok)

.filter_map(|line| {

let mut nums = line.split_whitespace().map(|x| x.parse::<i32>());

match (nums.next(), nums.next()) {

(Some(Ok(value1)), Some(Ok(value2))) => Some((value1, value2)),

_ => None,

}

})

.fold(

(Vec::new(), Vec::new()),

|(mut col1, mut col2), (v1, v2)| {

col1.push(v1);

col2.push(v2);

(col1, col2)

},

);

col1.sort_unstable();

col2.sort_unstable();

Ok((col1, col2))

}

The compute_distance function uses the zip function to combine iterators over both lists, and process the resulting iterator by taking pairs of numbers of each list, subtracting one from the other, taking the absolute value, and summing the resulting set of numbers. Rust combinator functions (map, filter, fold, flat_map, zip, reduce, …) are truly awesome at processing collections this way.

fn compute_distance(v1: &[i32], v2: &[i32]) -> i32 {

v1.iter().zip(v2).map(|(a, b)| (a - b).abs()).sum()

}

The read_lines function isn’t doing anything surprising either. We use a BufReader to achieve an iterator over the lines in the given file, and return this iterator in a Result:

fn read_lines<P>(filename: P) -> Result<Lines<BufReader<File>>>

where

P: AsRef<Path>,

{

let file = File::open(&filename)

.with_context(|| format!("Failed to open file: {:?}", filename.as_ref()))?;

Ok(BufReader::new(file).lines())

}

The Python code

It’s no surprise that, on the Python side, we have the same basic steps. The main function simply loops over all files, gets the sorted vectors and uses them to compute the total distance.

def main():

files = [

"./data/input_1k.txt",

"./data/input_10k.txt",

"./data/input_100k.txt",

"./data/input_1m.txt"

]

for file in files:

print(f"Processing {file}...")

start_time = time.time()

v1, v2 = get_sorted_vectors(file)

distance = compute_distance(v1, v2)

end_time = time.time()

elapsed_time_ms = (end_time - start_time) * 1000

print(f"The answer is: {distance}, completed in {elapsed_time_ms:.0f}ms\n")

The get_sorted_vectors function just reads all lines (this time without a separate function to read the file and return the buffered lines), extracts both numbers, and places them in their own lists. At the end, we return both sorted lists. By the way, granted, we could rename get_sorted_vectors to get_sorted_lists in the Python code, but I’ll let my prejudice shine through here. Speaking about superior methods of handling errors, goddamn, I do hate try-catch/try-except constructs… Errors are values! But I digress.

def get_sorted_vectors(file_path):

col1 = []

col2 = []

try:

with open(file_path) as f:

for line in f:

value1, value2 = map(int, line.split())

col1.append(value1)

col2.append(value2)

except ValueError as e:

raise ValueError(f"Error parsing the file: {e}")

except FileNotFoundError as e:

raise FileNotFoundError(f"File not found: {e}")

return sorted(col1), sorted(col2)

And the compute_distance function performs the required calculations to obtain the sum of all distances of every pair of entries:

def compute_distance(v1, v2):

return sum(abs(e1 - e2) for e1, e2 in zip(v1, v2))

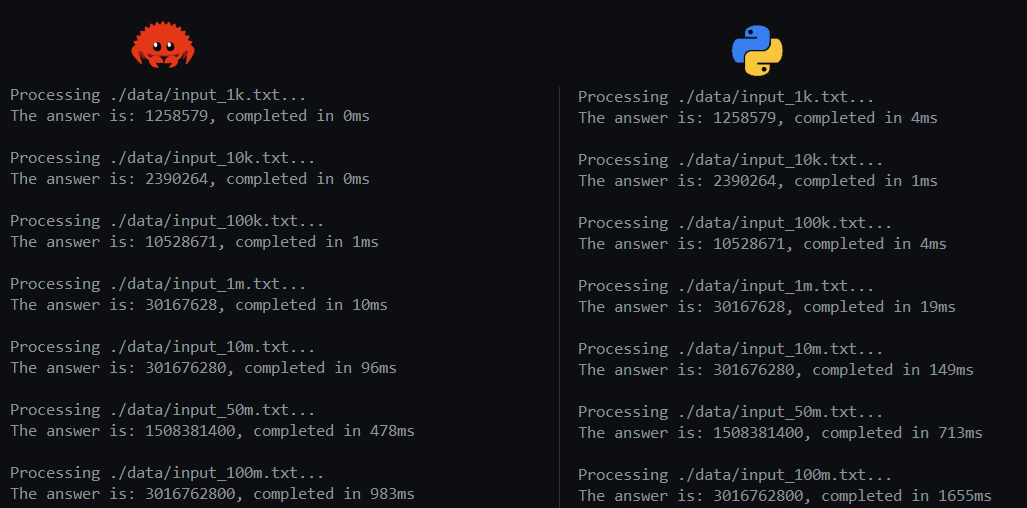

Even if you’re not that experienced in Rust or Python, I’m sure the code is quite easy to follow and reason through. Obviously, Rust was way faster, which should surprise nobody. Some initial results for the lists up to 1M items:

On the left half of the screenshot, you will simply see the timing of the Python implementation and the Rust implementation using only the standard library. Obviously, as we move up in scale towards 100k or 1M entries, you see that the difference between Python and Rust becomes bigger, which is already a serious hint towards the problems regarding scaling the Python implementation. On the other hand, whether we spend 68ms or 30ms on processing a list of 100k entries, is probably not that important. To spare Python, I won’t mention the resource use of both solutions (oops, I just did 😉), we all know how the picture would look. Python consumes substantially more memory and CPU. Let’s keep it fair and not focus on that right now; all we care about is processing speed at the moment.

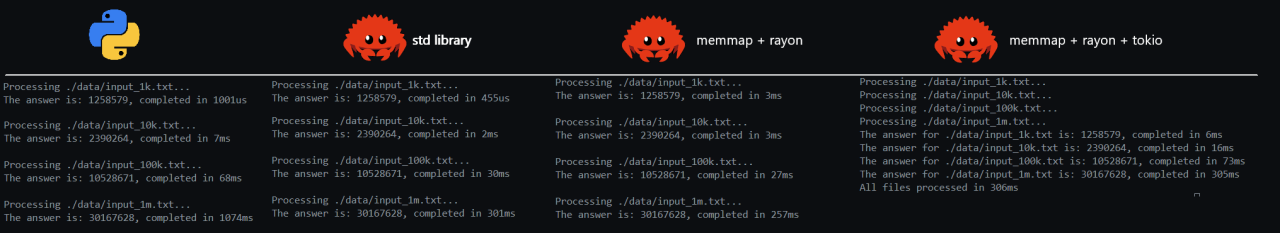

After this, I decided to try some other strategies on the Rust side, the results of which you will see on the right side of the screenshot:

- I used memmap to read the files instead of BufReader. This allows us to process the file as a memory-mapped file. Memory-mapped files allow you to map the file’s contents directly into the process’s address space. This enables accessing file data as if it were in memory, avoiding explicit read or write system calls. This enables handling files larger than the available physical memory by leveraging the operating system’s virtual memory system. This is particularly beneficial when working with datasets that are too large to fit into memory all at once. The results show that we clearly pay some overhead costs for the smaller files, but since we will be focusing on a bigger scale, this is worth it when we move towards millions of entries.

- To parallelise iteration of the lists, I used Rayon. Again, for smaller lists, the overhead of parallelisation would not be worth it. But for larger files, we would see a big speed-up.

You can see this result in the screenshot (memmap + rayon column). Additionally, I added tokio and processed all files concurrently. The results can be seen in the memmap + rayon + tokio column. I’ll not focus on concurrent handling of files, but I just wanted to add an example on how to combine Rayon and Tokio for this kind of work.

Where are we so far?

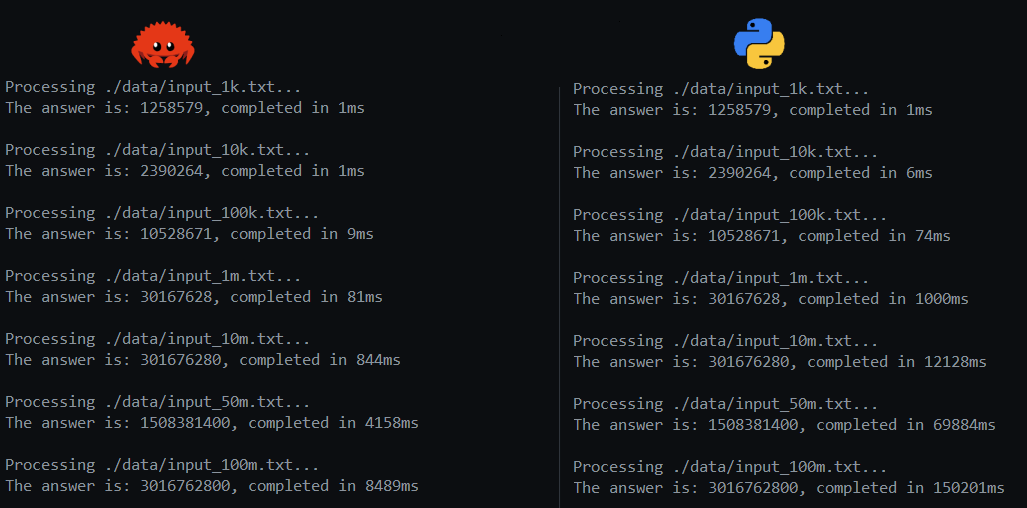

Now, processing 1 million lines is nice, but to really see the scalability of the implementations, let’s dial it up a few notches and increase the length of the files by a few orders of magnitude. I created some additional lists of 10M, 50M and 100M entries. To give you an idea of where we are at the moment, let’s run the current implementations for Rust and Python, up to 100M entries. This will help you appreciate the speed-ups that we will achieve in the work we will do in the upcoming sections.

To get an idea about the file sizes: the 100M entry file is about 1.3Gb in size. As you can see, the results are nothing to write home about. We need several seconds to process tens of millions of entries, and in the Python implementation we need several minutes. Quite abysmal, but this is to be expected, as we didn’t really put any effort into optimisation yet. On the Rust side, at least we are using Rayon and memmap to get a bit of a speed-up. The real work to achieve decent performance on either side is yet to be done though.

Let’s dial it up

Now, we all know Python is slow. Making the Python implementation fast is just not possible if we stick to “true Python”. So we won’t. We’ll use one of the (in my opinion at least) redeeming properties that Python has: it’s a great glue language. So, we will offload all the heavy lifting:

- Polars to load the files and parse each entry

- NumPy to calculate the distances

- Numba to speed up the remaining Python code.

In Rust, I tried to implement as much as possible myself, and tried to come up with improvements to avoid the annoying white space splitting and converting to numbers, and leveraged techniques like SIMD to crank out as much as I could. Some good old ingenuity and software engineering, or at least a brave attempt at it. A bit more of an artisanal approach, but I’d lie if I said that isn’t why I got into the profession.

Yeah, yeah yeah… Python

To get the Python implementation out of the way (I’m sorry, Pythonistas), there’s a few simple changes. The first thing that needs some explanation is probably the start of main. I’m calling the compute_distance function on 2 small hard-coded NumPy arrays. The reason for that is that the compute_distance function has the @jit attribute from Numba on it. This signifies that the function will be pre-compiled into C and executed as C code from then on. However, for that to happen, it needs to run 1 time for that pre-compilation to be triggered, which takes a bit of time. In order for us to not pay that cost while the actual data is processed, we execut the function on 2 small arrays to get the compilation done.

import time

import polars as pl

import numpy as np

from numba import jit

from concurrent.futures import ThreadPoolExecutor

def main():

# Warm-up call with small dummy inputs to precompile the Numba function

dummy_v1 = np.array([1, 2, 3], dtype=np.int64)

dummy_v2 = np.array([4, 5, 6], dtype=np.int64)

compute_distance(dummy_v1, dummy_v2) # This triggers the compilation

files = [

...

]

for file in files:

print(f"Processing {file}...")

start_time = time.time()

v1, v2 = get_sorted_vectors(file)

distance = compute_distance(v1, v2)

end_time = time.time()

elapsed_time_ms = (end_time - start_time) * 1000

print(f"The answer is: {distance}, completed in {elapsed_time_ms:.0f}ms\n")

The get_sorted_vectors function slightly changed as well. We use Polars to read the file, and push the data into NumPy arrays. This gets all splitting and parsing out of the way, and Polars will conveniently do it all for us. Additionally, we sort both arrays concurrently to achieve some speed-up there as well.

def get_sorted_vectors(file_path):

try:

df = pl.read_csv(file_path, separator=" ", has_header=False)

col1 = df[:, 0].to_numpy()

col2 = df[:, 1].to_numpy()

except ValueError as e:

raise ValueError(f"Error parsing the file: {e}")

except FileNotFoundError as e:

raise FileNotFoundError(f"File not found: {e}")

with ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=2) as executor:

future1 = executor.submit(np.sort, col1)

future2 = executor.submit(np.sort, col2)

sorted_col1 = future1.result()

sorted_col2 = future2.result()

return sorted_col1, sorted_col2

And finally, the compute_distance function, for what it’s worth, will be speed up using Numba. Now, we’re already speeding up the numerical operations with NumPy, but running the full function through Numba did result in some milliseconds of speed-up, so it was still worth it. In general, I recommend everybody wanting to perform some heavy computation (especially if it occurs in loops) to check out Numba. Before you do that, NumPy will probably get you very far, but it’s worth knowing about and experimenting with Numba. It allows you to dial in the speed of C without paying a heavy cost (as you can see, a simple attribute on the function in question is all you need). In the last implementation in the article, Numba will play a bigger role, stay tuned!

# Using Numba's JIT compiler to speed up the distance computation

@jit(nopython=True, cache=True)

def compute_distance(v1, v2):

return np.sum(np.abs(v1 - v2))

How about Rust?

Now things are about to get interesting. We’ll scale up our Rust code to be able to handle millions of entries, up to 100 million. We already did that for the Python implementation, by leveraging the power of NumPy, Polars and Numba to get as much as we can out of that solution. Now, we’ll do the same for Rust, but we’ll try to not use too many external dependencies. We could easily use ndarray as a Rust alternative to NumPy, and Polars in Rust.

However, the actual fun and learning in this kind of a challenge is found in expanding your own knowledge about how computers work, how to apply algorithms, and thinking outside of the box. It’s what brought technology to the point of having all the great things we have today, and it will serve us well into the future, so it’s not something we should take for granted. It helps I’m doing this in my own time, instead of on the companies’ dime 😉

So, let’s get to work! Without even doing the recommended thing and profile the application (always do this by the way!), I think we can all agree that this line of code:

line.split_whitespace().map(|x| x.parse::<i32>());

where we split every line in the file on the whitespace, and parse each side to an i32, will be a quite expensive operation. Especially since we know that we’ll do that millions of times. Let’s revisit our problem statement, more specifically our source data. We have a list of entries where each entry consists of a 5-digit number, a space, and another 5-digit number. That’s quite useful to know. If we could use this knowledge to avoid the splitting, and somehow also find a better way to do the parsing, this could save us a LOT of time! So, after some experimentation, I did just that. Let’s inspect the changes:

The get_sorted_vectors function uses memmap to treat the file as a memory-mapped file, as explained before. There’s still a split present, but we split on a newline character. The filter_map function now uses the parse_line function. We’ll send the resulting bytes of the split operation to parse_line, and we’ll parse the line there. The fold call did not substantially change. We’ll leverage rayon to sort both resulting lists, and we’ll sort each of them in parallel too.

fn get_sorted_vectors(file_path: &str) -> Result<(Vec<i64>, Vec<i64>)> {

let file = File::open(file_path).context("Failed to open file")?;

let mmap = unsafe { MmapOptions::new().map(&file)? };

let (mut col1, mut col2): (Vec<i64>, Vec<i64>) = mmap

.split(|&line| line == b'\n')

.filter_map(parse_line)

.fold((Vec::new(), Vec::new()), |(mut c1, mut c2), (a, b)| {

c1.push(a);

c2.push(b);

(c1, c2)

});

rayon::join(|| col1.par_sort_unstable(), || col2.par_sort_unstable());

Ok((col1, col2))

}

Now, about that parse_line function… I could understand if you wondered “what the hell is this” when reading the code below. However, knowing about the assumptions we made earlier about each line being identical in layout, should largely explain what’s happening. As said, the function receives an array of u8 bytes, representing our line of data. Since we assume that each line contains 2 5-digit numbers, separated by a space, we will return None whenever our amount of bytes is less than 11 (now I read that again, we should probably change that to bytes.len() != 11, but we’ll let that slide).

After that point in the code, we know we have 11 bytes to work with, and we know the byte at index 5 represents a space, so we can ignore it. We’ll take each entry in the byte-array and subtract b’0’ from it, which is the byte literal for the number 0. So we’ll convert the contents of that entry to its numeric value. The obtained digits are then scaled by their positional value:

- the first digit is multiplied by 10000

- the second digit is multiplied by 1000

- …

An example will explain it better: for bytes[0..5] = b”12345”, this calculates

1 * 10000 + 2 * 1000 + 3 * 100 + 4 * 10 + 5 = 12345

So we’ll obtain the actual number, without performing costly split_whitespace and parse operations. This works very well in our case, but is predicated on the ability of placing some strong assumptions on our input data. However, if we can guarantee things about our data, it often opens the door to tremendous speed-ups, as you will see soon.

A last remark. Looking at the code, some of you might think “well, you could implement this in a loop as well”. Of course, we can, but I preferred to do some loop unrolling. It doesn’t hurt clarity at all, in fact I would argue it makes the logic more explicit in this particular case. I have no doubt that our compiler could/would perform the same unrolling, but doing it manually does clarify the intention of our code better.

fn parse_line(bytes: &[u8]) -> Option<(i64, i64)> {

if bytes.len() < 11 { return None; }

let num1 = (bytes[0] - b'0') as i64 * 10000

+ (bytes[1] - b'0') as i64 * 1000 + (bytes[2] - b'0') as i64 * 100

+ (bytes[3] - b'0') as i64 * 10 + (bytes[4] - b'0') as i64;

let num2 = (bytes[6] - b'0') as i64 * 10000

+ (bytes[7] - b'0') as i64 * 1000 + (bytes[8] - b'0') as i64 * 100

+ (bytes[9] - b'0') as i64 * 10 + (bytes[10] - b'0') as i64;

Some((num1, num2))

}

In the compute_distance function, we just replace the .iter() call from the original implementation by the par_iter() equivalent from Rayon. Obviously, we can use the standard library to create a number of threads that would achieve the same, or very similar results, and process the lists in parallel. However, Rayon will do the annoying part of determining the number of threads and allocating memory for each of them for us, So the extra dependency is worth avoiding the annoying trial & error of determining the optimal setup. When running in constrained environments, know that this is perfectly viable to implement using the standard library. In the last implementation of the article, we’re actually performing a lot of the work manually after all, but for now, let’s keep it simple.

fn compute_distance(v1: &[i64], v2: &[i64]) -> i64 {

v1.par_iter().zip(v2).map(|(a, b)| (a - b).abs()).sum()

}

SIMD to the rescue

Before showing the comparative results between our handywork in Rust and the combination of NumPy, Polars and Numba, we’ll pull off one more trick, which is the use of SIMD. Some explanation on what SIMD is, can be found on Wikipedia or YouTube for a quick explanation. A longer lecture can be found right here. Warning here: to use SIMD, we’ll have to switch to the nightly build of Rust, as (at the time of writing), the SIMD implementations are not yet stabilised. This isn’t stopping us, of course.

So, how exactly can we use SIMD to speed up our code? Well, the parse_line function is particularly suited here. As you saw, we multiplied the entries of the byte-array with multiples of 10, depending on their position in the array, to obtain the actual number. What if, instead of multiplying each entry individually, we could perform this multiplication on all numbers in one single instruction? Of course, we would have to extract the right bytes out of the original array, but it’s worth checking whether the overhead from this extraction is amortised by the speed-up gained by the SIMD instruction. After some testing, it was very clear that it was worth it. So, I changed the parse_line function to the following implementation:

fn parse_line(bytes: &[u8]) -> Option<(i64, i64)> {

if bytes.len() < 11 {

return None;

}

let num1_simd = i32x8::from([

(bytes[0] - b'0') as i32, (bytes[1] - b'0') as i32,

(bytes[2] - b'0') as i32, (bytes[3] - b'0') as i32,

(bytes[4] - b'0') as i32, 0, 0, 0

]);

let num2_simd = i32x8::from([

(bytes[6] - b'0') as i32, (bytes[7] - b'0') as i32,

(bytes[8] - b'0') as i32, (bytes[9] - b'0') as i32,

(bytes[10] - b'0') as i32, 0, 0, 0

]);

// SIMD vector for powers of 10 for multiplication

let powers_of_ten = i32x8::from([10000, 1000, 100, 10, 1, 0, 0, 0]);

// Do the multiplication

let num1 = (num1_simd * powers_of_ten).reduce_sum() as i64;

let num2 = (num2_simd * powers_of_ten).reduce_sum() as i64;

Some((num1, num2))

}

We can also change our compute_distance function to leverage SIMD, to some extent. Before, we simply used Rayon to compute the distances in parallel:

fn compute_distance(v1: &[i64], v2: &[i64]) -> i64 {

v1.par_iter().zip(v2).map(|(a, b)| (a - b).abs()).sum()

}

But the implementation below did prove to be quite a bit faster. We still use Rayon (as you can see by the into_par_iter() call), but we also manually chunk our input arrays, and calculate the differences using SIMD vectors.

- the subtraction of the two SIMD vectors (v1_simd - v2_simd) is done in a vectorized manner. This means that the CPU performs 8 subtractions in parallel for the 8 corresponding elements of v1 and v2 in each chunk.

- the .reduce_sum() function is used to sum up the 8 values in the SIMD vector diff. This operation reduces the SIMD vector to a single scalar value, which is the sum of the absolute differences for that chunk. The use of SIMD reduces the number of individual addition operations by performing 8 additions in parallel.

- After processing the chunks, any remaining elements (if the total length isn’t a multiple of CHUNK_SIZE) are handled in a regular, sequential manner. This ensures that no elements are left out of the calculation.

fn compute_distance(v1: &[i64], v2: &[i64]) -> i64 {

const CHUNK_SIZE: usize = 8; // Changed to match SIMD vector size

let len = v1.len();

let chunks = len / CHUNK_SIZE;

let sum: i64 = (0..chunks)

.into_par_iter()

.map(|i| {

let start = i * CHUNK_SIZE;

let v1_simd = i64x8::from_slice(&v1[start..start + CHUNK_SIZE]);

let v2_simd = i64x8::from_slice(&v2[start..start + CHUNK_SIZE]);

let diff = (v1_simd - v2_simd).abs();

diff.reduce_sum()

})

.sum();

// Handle remaining elements if any

let remainder_sum: i64 = (chunks * CHUNK_SIZE..len)

.map(|i| (v1[i] - v2[i]).abs())

.sum();

sum + remainder_sum

}

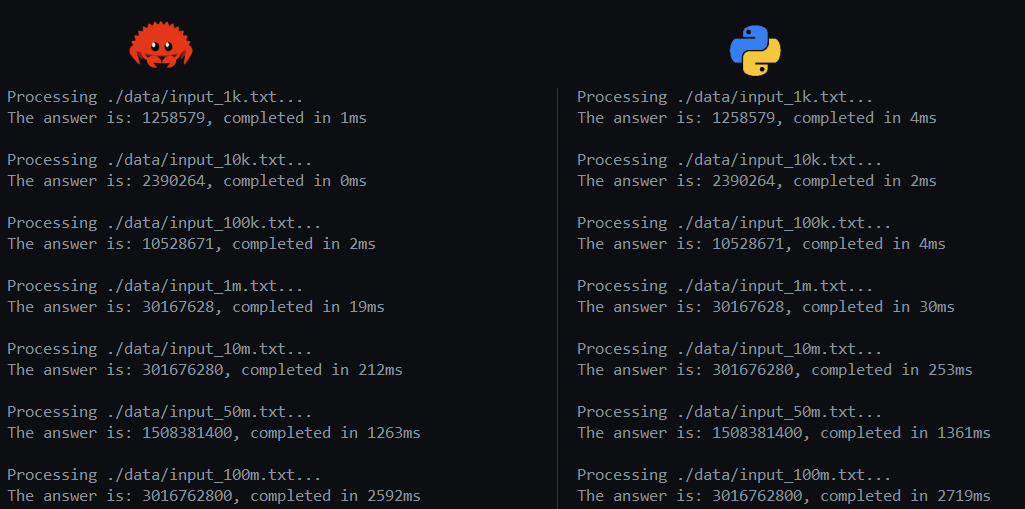

The results: Rust on the left, Python on the right. Racing through and processing 100 million entries (a 1.3Gb file) in 2.6 secs is pretty satisfying. I was able to get it down to 2.7 secs with Python, but again, literally all the code that actually does something is in Numpy or Polars, and I’m using Numba to precompile the functions to C. So it’s basically my own implementation in Rust versus the fastest possible frameworks in Python written in C and Rust, glued together.

So, about Polars…

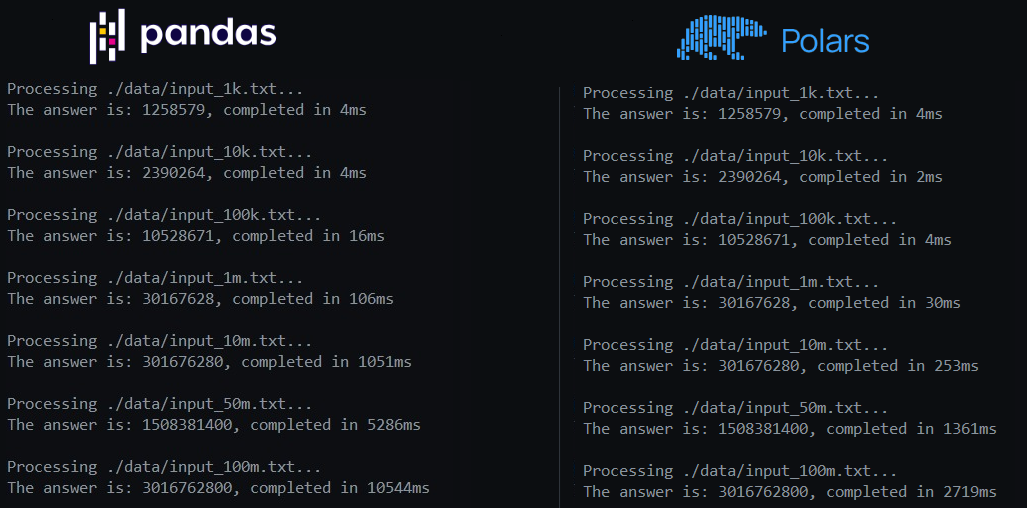

As an aside, talking about Python frameworks: Pandas is known as the reference Python library for data processing. A while ago (at the time of writing), Polars came out as a solid alternative. It’s implemented in Rust, and offers quite a bit of speed-up compared to Pandas. It’s available in Rust, but also has great Python bindings. To demonstrate, I took the code that resulted in the numbers above on the Python side, and changed 1 thing: I threw out Polars and used Pandas to read the files. The difference in code is absolutely minimal. The difference in performance, though, doesn’t paint the prettiest picture for Pandas:

Again, this is the same Python code on both sides, and the only difference is the use of Pandas instead of Polars. The change in code:

df = pl.read_csv(file_path, separator=" ", has_header=False)

versus

df = pd.read_csv(file_path, sep=" ", header=None)

This should probably encourage you to at least check out Polars as a drop-in replacement for Pandas. You can check out more about Polars here.

Algorithms!!

After implementing the code above, I was actually quite happy with the results so far. I mean, zipping through a 1.3 Gb file (for the 100M entries) in 2.5 seconds isn’t too shabby, is it? However, I then did myself in by deciding to check the time it took to only read the file. For the 100M file, just reading and not processing anything took about 1.3 seconds. Humble pie right there. For sure I could shave some time off that 1.2 seconds of processing…!? So, I went back to the drawing board and checked if I could use the assumptions I put on the data to get even faster.

My intuition immediately went to the sorting part of the work. The whole parsing exercise is probably quite efficient already, but could we sort the lists in a more time-efficient way? At first, I thought about implementing a min binary heap. But, then again, we do need to obtain the whole list as a sorted list eventually, so that’s probably a no-go. The current sorting method that’s executed by par_sort_unstable is a pattern-defeating quicksort, which combines the fast average case of randomised quicksort with the fast worst-case of heapsort. On average, we are still bound to a O(n log n) running time. We’re still doing a comparative sort. However, what if we can get away by not doing a comparative sort? It turns out that, since we know a thing or 2 about or input data, we can!

Bucket sort

Bucket sort is a sorting algorithm that works by distributing the elements into a number of buckets (or “bins”) and then sorting each bucket individually. The key idea behind bucket sort is that it divides a large problem into smaller, easier-to-solve subproblems and then combines the results to get the final sorted array. It is especially efficient when the input elements are uniformly distributed across a range.

And it just so happens that the range of our input elements is indeed well-known. Since all our input elements are 5-digit numbers, all of them are between 10,000 and 99,999. So, we can use the principles behind bucket sort, such as bucketing and efficient lookup, without explicitly sorting the entire data set. That’s worth a go!

The implementation

Here is the implementation in Rust. There are several steps:

- first, we’ll define the range of our inputs, which is between 10,000 and 99,000.

- then, we create the buckets as vectors, each of size equal to the range. These buckets will store the counts of occurrences of each number in the respective lists.

- we’ll memory-map the file, as we did before

-

we’ll then process each line and populate the buckets. For each line, we parse the two 5-digit numbers with the familiar parse_line function. The numbers are mapped to their corresponding index in the buckets by subtracting MIN_VAL. This essentially “places” the number in the appropriate bucket based on its value.

For example, if num1 is 10,123, it will go to index 10,123 - 10,000 = 123.

- we’ll then perform bucket matching: The function iterates over all the buckets (i from 0 to RANGE). For each bucket:

- we check if there are any remaining numbers in buckets1[i].

- we then look for a non-zero bucket in buckets2 starting from j. This is similar to matching elements from two sorted sets, which is done by traversing both buckets1 and buckets2 in a greedy fashion.

- when a matching number is found, we calculate the absolute distance between num1 and num2, add this to total_distance, and decrease the count in both buckets1[i] and buckets2[j].

- the j pointer ensures that buckets2 is traversed efficiently, skipping over empty buckets. This helps avoid unnecessary comparisons and speeds up the matching process.

Instead of sorting the entire set of numbers (which would take O(n log n) time), this approach works by counting occurrences of each number and then processing them in a way that avoids the overhead of comparison-based sorting. This results in a worst-case time complexity of O(n²) when all elements fall into a single bucket (which would be an absolute disaster). However, on average with good distribution, we can achieve O(n). Learn more about bucket sort here.

fn compute_distance(file_path: &str) -> Result<i64> {

// Define the range for 5-digit numbers

const MIN_VAL: i64 = 10_000;

const MAX_VAL: i64 = 99_999;

const RANGE: usize = (MAX_VAL - MIN_VAL + 1) as usize;

// Initialize buckets

let mut buckets1 = vec![0i64; RANGE];

let mut buckets2 = vec![0i64; RANGE];

// Open file and memory-map it

let file = File::open(file_path).context("Failed to open file")?;

let mmap = unsafe { Mmap::map(&file).context("Failed to memory-map file")? };

// Process lines from the memory-mapped file

for line in mmap.split(|&byte| byte == b'\n') {

if !line.is_empty() {

if let Some((num1, num2)) = parse_line(line) {

buckets1[(num1 - MIN_VAL) as usize] += 1;

buckets2[(num2 - MIN_VAL) as usize] += 1;

}

}

}

// Compute total distance

let mut total_distance = 0;

let mut j = 0;

(0..RANGE).for_each(|i| {

while buckets1[i] > 0 {

while j < RANGE && buckets2[j] == 0 {

j += 1;

}

if j < RANGE {

let actual_num1 = i as i64 + MIN_VAL;

let actual_num2 = j as i64 + MIN_VAL;

total_distance += (actual_num1 - actual_num2).abs();

buckets1[i] -= 1;

buckets2[j] -= 1;

}

}

});

Ok(total_distance)

}

For Python, we’ll once again annotate the function with @jit to compile it in C and get the most speed-up we can.

@jit(nopython=True, cache=True)

def compute_distance(col1, col2):

# Define the range for 5-digit numbers

MIN_VAL = 10_000

MAX_VAL = 99_999

RANGE = MAX_VAL - MIN_VAL + 1

# Initialize buckets

buckets1 = np.zeros(RANGE, dtype=np.int64)

buckets2 = np.zeros(RANGE, dtype=np.int64)

# Populate buckets

for num in col1:

buckets1[num - MIN_VAL] += 1

for num in col2:

buckets2[num - MIN_VAL] += 1

# Process buckets

total_distance = 0

j = 0

for i in range(RANGE):

while buckets1[i] > 0:

while j < RANGE and buckets2[j] == 0:

j += 1

if j < RANGE:

actual_num1 = i + MIN_VAL

actual_num2 = j + MIN_VAL

total_distance += abs(actual_num1 - actual_num2)

buckets1[i] -= 1

buckets2[j] -= 1

return total_distance

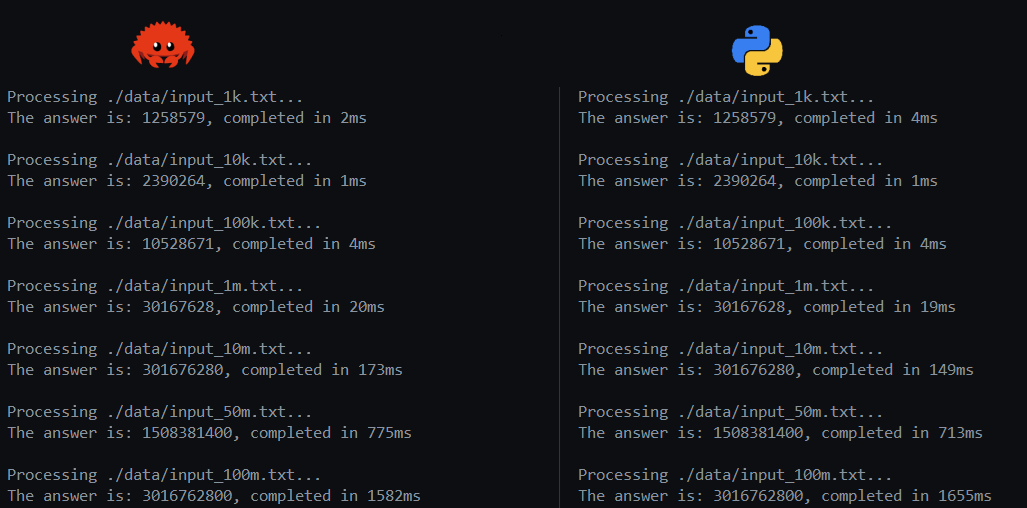

These efforts resulted in the measurements shown below. I was quite happy to see that my Rust implementation could still keep up and at times outwork the Python implementation. In the end, after running both implementations many times, it was clear that there was hardly a difference between both. However, knowing that Python relies completely on C or Rust libraries, and most of the work on the Rust side was done by myself, was quite satisfying. Really looking at your source data and continuously learning about algorithms and techniques like SIMD, are never wasted efforts.

One final touch

After inspecting the code one final time, I did notice a few more things I could improve. Mainly, this following bit in the compute_distance function:

for line in mmap.split(|&byte| byte == b'\n') {

if !line.is_empty() {

...

}

...

}

We’re being all efficient with our parsing of lines, looking at the individual bytes and avoiding calling parse functions. But we’re still splitting on \n… Additionally, we’re testing every line to see if it’s empty. Since we’ve been relying on some assumptions regarding our input data, let’s continue that trend and optimise these last few issues as well. After all, splitting the entire file on these returns, and testing if each line is empty, will be costly, and we should try to avoid it or perform these steps more efficiently.

We make the assumption that each line

- is 13 bytes long

- consists of 5 digits, a space, another 5 digits, and a \n to get to the next line

Let’s really use that to avoid all splitting whatsoever. We’ll use the chunks_exact function to step through the file in 13-byte chunks. For each chunk, we’ll simply parse the bytes, and bucket the obtained numbers.

fn compute_distance(file_path: &str) -> Result<i64> {

// Define the range for 5-digit numbers

const MIN_VAL: i64 = 10_000;

const MAX_VAL: i64 = 99_999;

const RANGE: usize = (MAX_VAL - MIN_VAL + 1) as usize;

// Initialize buckets

let mut buckets1 = vec![0i32; RANGE];

let mut buckets2 = vec![0i32; RANGE];

// Open file and memory-map it

let file = File::open(file_path).context("Failed to open file")?;

let mmap = unsafe { Mmap::map(&file).context("Failed to memory-map file")? };

// Since we know the exact length in bytes of each line, we can simply step through it

const STEP: usize = 13;

for line in mmap.chunks_exact(STEP) {

if let Some((num1, num2)) = parse_line(line) {

unsafe {

*buckets1.get_unchecked_mut((num1 - MIN_VAL) as usize) += 1;

*buckets2.get_unchecked_mut((num2 - MIN_VAL) as usize) += 1;

}

}

}

// Compute total distance

let mut total_distance = 0i64;

let mut j = 0;

(0..RANGE).for_each(|i| {

while buckets1[i] > 0 {

while j < RANGE && buckets2[j] == 0 {

j += 1;

}

if j >= RANGE {

break;

}

let count = buckets1[i].min(buckets2[j]);

total_distance += count as i64 * (i as i64 - j as i64).abs();

buckets1[i] -= count;

buckets2[j] -= count;

}

});

Ok(total_distance)

}

Let’s also change the way we parse lines. Nothing overly crazy, however: we’ll remove the use of SIMD from handling of the byte arrays, and we’ll instead sprinkle some unsafe code in there. For readability, I moved the parsing portion of our logic to another function. We’ll annotate it with an inline(always) attribute, so that the compiler always inlines the code instead of having millions of calls to a separate function. Some experimentation showed that these changes also shaved of some tens of milliseconds on the largest files.

fn parse_line(bytes: &[u8]) -> Option<(i64, i64)> {

if bytes.len() < 13 || unsafe { *bytes.get_unchecked(5) } != b' ' {

return None;

}

// Unsafe slice access (validated by line length check)

let num1 = parse_digits(unsafe { bytes.get_unchecked(0..5) })?;

let num2 = parse_digits(unsafe { bytes.get_unchecked(6..11) })?;

Some((num1, num2))

}

#[inline(always)]

fn parse_digits(bytes: &[u8]) -> Option<i64> {

if bytes.len() != 5 {

return None;

}

// Safe to parse now

let d0 = (bytes[0] - b'0') as i64;

let d1 = (bytes[1] - b'0') as i64;

let d2 = (bytes[2] - b'0') as i64;

let d3 = (bytes[3] - b'0') as i64;

let d4 = (bytes[4] - b'0') as i64;

Some(d0 * 10000 + d1 * 1000 + d2 * 100 + d3 * 10 + d4)

}

And this results in the final set of results I will show you. I’m glad to see that these last set of changes decreased the time spent by another 35-40%, which is pretty amazing. However, I hope some of you can completely leave my Rust implementation in the dust and introduce massive speedups (maybe using the GPU, even more interesting and innovative algorithms or approaches, …). Again, if so, definitely contact me; I always want to learn. For the time being, on my machine, loading the file and processing 100 million entries takes about 1 second, which is fine by me. Thanks for reading through the entire article; I hope it sparked your interest!